In our day, the dominant tradition concerning eternal punishment is that of Eternal Conscious Torment (ECT). I do not hold to it. In my view, annihilationism aligns more closely with the biblical data, for several compelling reasons. Of course, not all forms of annihilationism are identical, so to be perfectly clear: I believe that unbelievers will be resurrected in order to face judgment and receive punishment, which will vary in degree and duration according to their deeds. Thereafter, they will undergo the second death—that is, final and irreversible destruction.

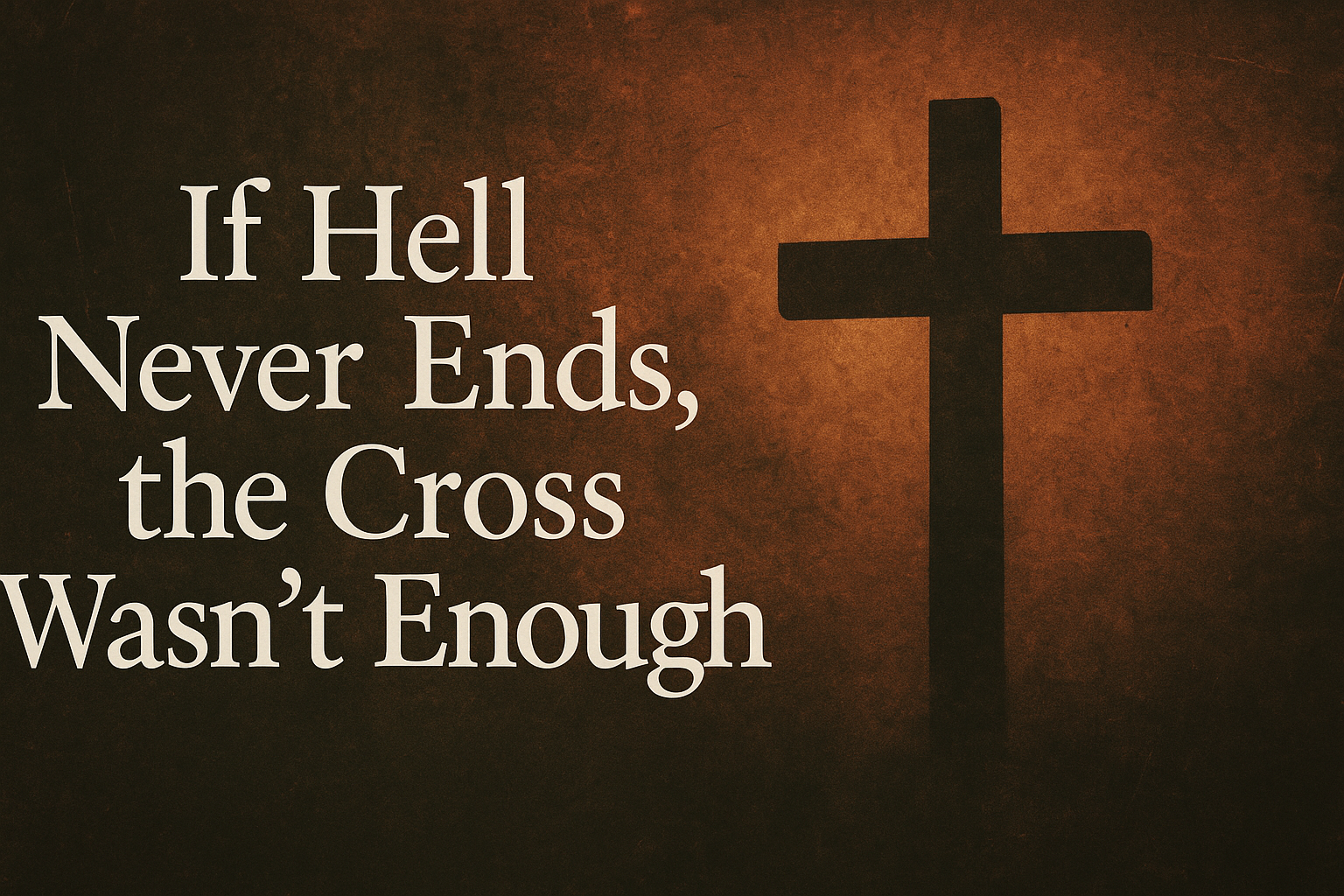

There are many arguments for and against annihilationism—ranging from lexical studies of the word apollumi to the moral intuition that endless torment seems irreconcilable with a God of love. But even if one set aside all those debates, the doctrine of substitutionary atonement alone (intended here in a sense broader than Penal Substitutionary Atonement (PSA)) renders ECT untenable.

If Jesus was truly our scapegoat (Lev. 16), our substitute, the One who bore the penalty in our place, then logic demands that He suffered what we deserved. However, if Eternal Conscious Torment (ECT) is true, then Jesus did not really pay for the sins of the world.

This statement rests on a theological and moral analysis of what it means for Jesus to have borne the penalty of sin on behalf of humanity. Scripture repeatedly affirms that Jesus, the Lamb of God, “takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29), and that “He Himself is the propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only, but also for those of the whole world” (1 John 2:2). Yet if ECT is true—if the final punishment for the unsaved is endless, conscious torment—then what, precisely, did Christ bear on the cross?

The core problem is this: a punishment that is infinite in duration cannot be said to have been borne or paid for unless it is somehow compressed, exhausted, or extinguished. But the ECT view maintains that the punishment for sin is not merely infinite in consequence, but eternal in experience. It continues without end. If that is so, then Christ could not have endured it in our stead. He was crucified, died, and rose again the third day. His suffering, though immense and of unfathomable depth, was not eternal in duration. Therefore, if eternal torment is the actual penalty of sin, then Christ did not pay that penalty. At most, He experienced a different kind of suffering.

One might attempt to respond that Christ, being divine, could compress the infinite into finite time. But this undermines the analogy of substitution. A substitute must undergo the same punishment that the guilty deserve, or else the justice of the substitution is compromised. If I am condemned to life in prison, and a substitute offers to pay my debt by spending a weekend in jail, no one would say justice has been satisfied. The supposed solution—compression—makes a mockery of proportionate justice.

Furthermore, this undermines the Gospel’s bold claim that Jesus “tasted death for everyone” (Heb. 2:9). If ECT is the second death (Rev. 20:14), and if that death is eternal conscious torment, then Jesus did not taste it—He avoided it. But if death, in biblical terms, is cessation of life—the loss of conscious experience—then Jesus’ real death on the cross is a suitable and satisfying substitute.

Thus, theologically, morally, and biblically, ECT renders the atonement incomplete or unjust. Either Jesus did not pay the full penalty (if ECT is true), or ECT misrepresents the true nature of that penalty. One must choose: either Christ truly paid it all, or sinners will go on paying what He did not.

The cross compels us to conclude the latter is false. Jesus paid it all.

Leave a Reply