When someone leaves a congregation, the instinctive reaction is often defensive and self-protective. The narrative forms quickly and predictably. The person who left is assumed to be at fault. They lacked maturity. They resisted authority. They grew spiritually dry. They did not want to serve. They were unwilling to sacrifice. In short, their departure is framed as evidence of their spiritual failure rather than as a moment of sober self-examination for the community they left.

That reflex is not neutral. It is a form of self-righteousness. It shields the group from accountability by placing all responsibility on the individual who walked away. Once this story is accepted, no repentance is required, no correction is needed, and no listening must take place.

My experience suggests a different and far more uncomfortable conclusion.

When someone leaves a church, the congregation or its leadership is often at fault.

This is not to deny that people sometimes leave for questionable reasons. It is to challenge the near-automatic assumption that the problem must lie with the one who left rather than with the environment they were in. A church that consistently interprets departures as proof of others’ spiritual deficiency may in fact be revealing its own blindness.

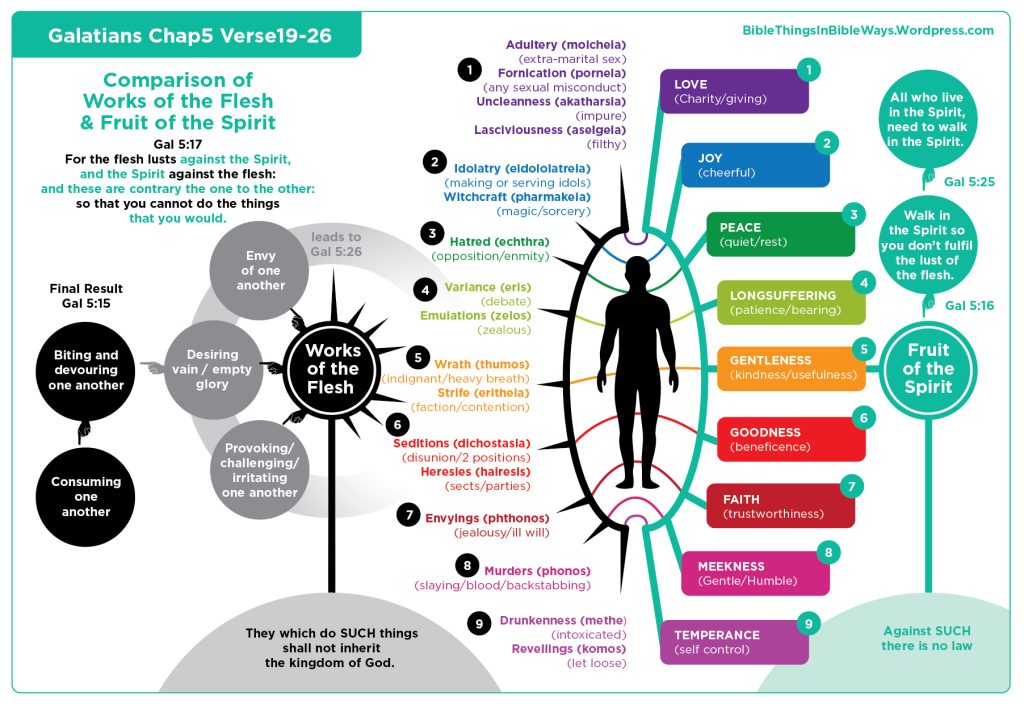

The apostle Paul offers a sobering diagnostic tool in Galatians 5. He does not describe church health in terms of activity, visibility, influence, or numerical growth. He contrasts two realities that manifest themselves in community life: the deeds of the flesh and the fruit of the Spirit. These are not abstract theological categories. They are relational realities that become visible wherever people live closely together.

What is striking is how easily the deeds of the flesh can thrive under religious language and structure. Envy, jealousy, rivalry, anger, ambition, sectarianism, pride, and hypocrisy often appear not as obvious vices but as zeal, discernment, strong leadership, or doctrinal faithfulness. They are baptised, normalised, and sometimes even rewarded. Meanwhile, the fruit of the Spirit remains comparatively rare, fragile, and costly.

Many people do not leave churches because they want less commitment, less holiness, or less truth. They leave because they are starving for love, kindness, patience, gentleness, and peace, and instead encounter suspicion, control, competition, moral posturing, and relational coldness. They are told about grace while being measured by performance. They are exhorted to unity while navigating unspoken hierarchies and power struggles. They are encouraged to be honest while learning that honesty comes at a relational cost.

In such contexts, leaving is not rebellion. It is often survival.

A congregation marked by the Spirit’s fruit does not need to defend itself when someone leaves. It listens. It grieves. It examines itself honestly. It asks whether its life together reflects the character of Christ or merely the preservation of a system. A church dominated by the flesh, by contrast, cannot tolerate this kind of reflection. It must explain departures in moral or spiritual terms because acknowledging failure would threaten its self-image.

If the fruit of the Spirit were truly abundant in our churches, departures would be rarer, and when they did occur, they would be handled with humility rather than judgement. The tragedy is not that people leave congregations. The deeper tragedy is when they leave wounded, disillusioned, and convinced that what they experienced was Christianity itself.

In that sense, the question is not why so many walk away, but why we are so reluctant to ask what they were walking away from.

Leave a Reply