The tragedy of our day is that the simple gospel has been increasingly overshadowed by a pernicious emphasis on subjective experience. I have already observed that this error has led to confusion and doubt, particularly concerning the question of baptism and the assurance of salvation. Yet the problem is even broader. It affects the very heart of how we view conversion itself.

An increasingly common notion among some Christians is that true conversion must be accompanied by a discernible, emotional “experience” with the Lord. Without such an experience, they argue, a person’s faith cannot be deemed genuine. This position is not merely mistaken; it is absurd, and borders on evil.

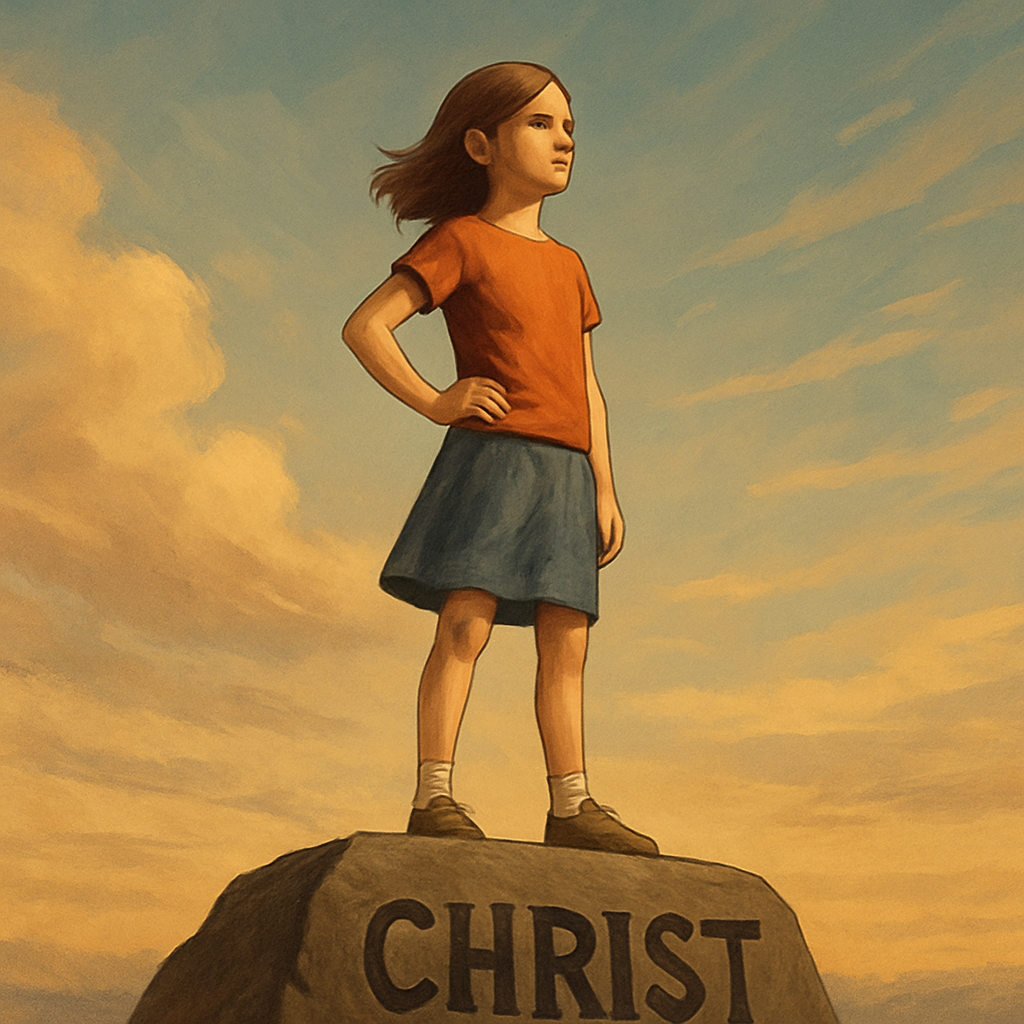

Consider a young girl who grows up in a Christian home. From an early age she has been taught the gospel, and she confesses with sincerity that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing she has eternal life (John 20:31). Yet, because she does not recount a dramatic emotional encounter or a specific “moment of overwhelming feeling,” she is told by some that she is not truly converted.

This is nothing short of spiritual abuse. It betrays a profound misunderstanding of the gospel, which is grounded not in our experience, but in the objective promise of God. Salvation is not authenticated by the turbulence or intensity of our emotions, but by the sure word of Christ: “He who believes in Me has everlasting life” (John 6:47).

This is not to deny that genuine spiritual experiences do occur. Many believers, at various points in their Christian walk, encounter profound moments of intimacy with the Lord—seasons of renewal, conviction, calling, or deeper consecration. Yet these experiences must not be made prescriptive of conversion itself. Often such encounters do not mark the moment of salvation, but rather later stages of spiritual maturation: the acknowledgment of a calling, the realisation of a need to walk more closely with Christ, the decisive turning from waywardness to a more deliberate discipleship. To confuse these vital aspects of growth with the initial moment of faith is to conflate two distinct realities.

Scripture abounds with examples of faith grounded in truth, not emotional spectacle. Timothy, for instance, “from childhood” knew the Holy Scriptures, being taught by his faithful mother and grandmother (2 Timothy 1:5; 3:15), yet no dramatic emotional conversion experience is recorded. Likewise, the Bereans “received the word with all readiness,” and diligently searched the Scriptures daily (Acts 17:11), rather than seeking an emotional event.

The absurdity of the “experience-centred” view becomes all the more evident when we consider that not all human beings are even capable of experiencing emotions in the same way. Take, for instance, David Wood, a well-known Christian apologist and polemicist against Islam. He has openly spoken of his diagnosis as a psychopath, which entails an inability to feel a normal range of emotions. Are we to conclude that men such as Wood cannot be (or are not truly) saved simply because they do not feel as others do? Such a position would be monstrously unjust, and would contradict the very nature of grace itself.

Moreover, Scripture nowhere demands that an emotional experience be added to faith for salvation. On the contrary, we are told again and again that “whoever believes” has eternal life. No qualifiers, no emotional requirements. Faith itself is “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (Hebrews 11:1), not the evidence of things felt.

To make emotional experience central is to introduce a new legalism into the Church. Just as the Pharisees burdened men with traditions and external requirements, so too does this doctrine burden souls with the demand for inward emotional performance. Assurance is shifted from the finished work of Christ to the unstable grounds of personal feeling.

God has created human beings with a wide diversity of emotional constitutions. Some are naturally more reflective and reserved. Others have neurological or psychological conditions—such as autism spectrum disorders, psychopathy, or trauma-related emotional impairments—that affect how emotions are processed. The God who knit each person together in the womb does not require of His creatures that which He has not equipped them to produce. To insist otherwise is to slander the Creator Himself.

Throughout history, wise theological voices have warned against basing assurance on feelings. Charles Spurgeon admonished his hearers that feelings are unstable, whereas Christ’s work is steadfast.

I do not hang upon my feelings, I rely simply upon Christ; and I must learn the difference between feeling and believing, or else I shall always be blundering and making mistakes.

— Charles Spurgeon in Faith Versus Sight

Martin Luther, plagued by subjective despair, learned to rest not in the shifting sands of his internal condition but in the external promise of Christ.

The long-term pastoral consequences of an experience-centred gospel are devastating. Young believers are discouraged, some turning away altogether, others manufacturing false experiences to “fit in,” searing their consciences and planting the seeds of future doubt. Churches become gatherings not of those who believe the truth, but of those who share a similar emotional narrative.

We must resist this error with all our strength. Let us proclaim again that salvation is by grace alone, through faith alone, in Christ alone—not through feelings, not through experiences, but through the unbreakable promise of the faithful God who cannot lie.

“The one who comes to Me I will by no means cast out” (John 6:37). That is the ground of our assurance. Nothing else is needed. Nothing else is permitted.

Post Scriptum

A final word is needed regarding the nature of emotional or transformative experiences. It must be remembered that the subjectivity of an experience neither proves the reality of one’s faith nor the truthfulness of one’s belief system.

Many who undergo profound emotional transformations, marked by discipline, new purpose, and even outward moral improvement, do so under the banners of religions and ideologies far removed from the truth of the gospel.

One thinks, for example, of Malcolm X, whose conversion to the Nation of Islam brought about a radical change in his life, abandoning crime, embracing discipline, advocating for justice. Yet the theological system to which he converted was rife with grave errors. His transformation was undeniable; but it did not prove the truth of his creed.

Likewise, countless individuals testify to profound experiences within the framework of Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, or New Age movements; experiences that they interpret as confirmation of the truth of their respective paths.

If subjective experience were the measure of truth, every system would be equally validated, and Christ’s unique claims rendered meaningless.

But the gospel does not rest upon the instability of human emotion. It rests upon the objective reality of Christ’s death and resurrection, historic events attested by witnesses, declared in Scripture, and offered to all who believe, apart from the need for a particular feeling.

Leave a Reply